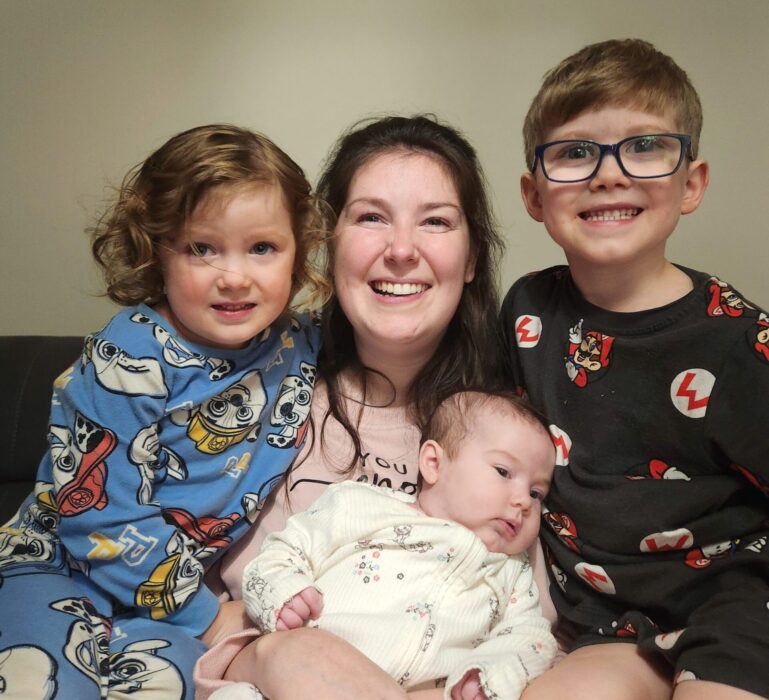

Lucy Lintott Smith was just 19 when she was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease (MND), making her the youngest person in Scotland to be diagnosed with the terminal neurological condition. Editor Melissa Holmes caught up with Lucy, soon after the birth of her third child

Being diagnosed with a progressive, terminal condition at the age of just 19 would change anyone’s perspective on life. Scotland-based Lucy Lintott Smith recently turned 30, had her third child, and hit the incredible milestone of 11 years since her diagnosis of MND. “It’s still very surreal,” admits Lucy. “It had never been in my future planning to get to 11 years. I was so fixated on the 10 years. I was told 18 months… so to get 11 years is just unreal.”

People with MND experience a range of symptoms, including weakness in their ankle, leg or hand grip, weight loss, slurred speech and muscle cramps. It happens when cells in the brain – the motor neurones – gradually stop working over time, and mainly affects people in their 60s and 70s. It limits life expectancy, and there is no cure.

Lucy acknowledges that her symptoms are “probably worsening all the time. Mine’s so slow that it’s not really recognisable. If you see me sporadically, like once a year, then you’d notice my speech was a little bit worse, for example.” She says some days are better than others, but she misses being able to be on autopilot: “You know, when you’re busy and your mind and body just take over,” she reflects. “I can’t do that anymore. I want to snap out of it, get on and do things, but I can’t. That’s probably the most frustrating thing.”

MILESTONES

So what’s kept Lucy going, and helped her beat the odds? “I think one of the main reasons I’m still here and haven’t given up is because of the kids,” she says. “Seeing their milestones helps me get through. Being a mum, you can’t stay in bed. You’ve got to get up, feed them, wash them, entertain them and tidy up after them all day long.”

Conceiving and birthing three children naturally is a challenge for any person, but when you have MND, it’s kind of miraculous. In September 2024, Lucy and her husband Tommy welcomed their third child into the world. They now have three children under five, although Lucy was told her body would never handle pregnancy.

SURPRISE

She told us: “This pregnancy was such a surprise. We chose to keep this one to ourselves till after she was born, to have some normality.” She describes recovery from the birth as “harder than the other two – it’s hard to know what’s MND and what’s actually labour. I’ve never been good with the lack of sleep, and she’s really testing that.”

Lucy is a full-time wheelchair user, and her care package hasn’t changed since her daughter was born. “A lot of it falls on my husband,” she admits. “He does everything and is there every day, he gets all the rubbish jobs – I think I’ve changed one nappy; he’s always changed every nappy.”

All the same, Lucy gives her all to her kids, from cuddles in her powerchair while she moves her legs to help relieve her little one’s colic, being there for them every day. What does she find most rewarding about motherhood? “That’s a hard one!” she laughs. “Probably the way you see them develop as a person. Like my son, he used to hate water and swimming. But we took him to lessons every week and he can now put his face under the water. It seems such a small thing, but because it’s taken him so long to get to that point, it’s so rewarding.”

CHANGED PERSPECTIVE

She believes her perspective on life has changed a lot since she became a mother. “I don’t dwell on the small things anymore,” she confesses. “I don’t know what it is – you grow up and you just don’t care as much. That sounds bad, but I mean about other people’s opinions – I’m like ‘oh well!’.”

Over the years, Lucy has raised thousands for charities like MND Scotland, and has used her blog, a TV programme, speaking opportunities and her social media to raise awareness about life with the disease, which affects up to 5,000 adults in the UK at any one time.

She’s taking a break from her fundraising efforts for now – an epidural during birthing has caused some ongoing pain. But that doesn’t mean she’s not keeping herself busy. “I’ve already done the first year of an accounting degree,” she explains. “Hopefully the degree will be done by the time my youngest is in school.” Lucy’s resilience and drive are impressive, and she says: “I don’t cope well mentally when I’m not doing stuff. I get tired easily physically, but mentally if I’m not doing things then I can’t sleep.”

And as for her hopes and dreams further into the future? Lucy wants the same as everyone else. “It goes without saying that I hope there’s a cure soon,” she reveals. “There are a lot of trials being done; I just hope one of them can either reverse MND or stop it in its tracks.” This would be lifechanging: “It would be more lifechanging for the ones that haven’t yet been diagnosed. It’s such a hard thing, being diagnosed as terminal: they tell you ‘There’s nothing we can do’, and then you’ve just got to get on with it. It’s probably the hardest thing to comprehend.”